|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

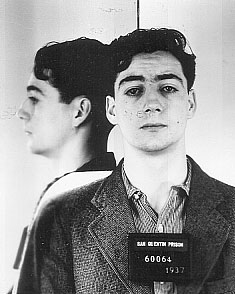

The following is excerpted from The California Snatch Racket: Kidnappings in the Prohibition and Depression Eras  Baby Bandits — it must have been humiliating for youngsters in their late teens to read

that term. Nevertheless, a clever reporter gave the name to a collection of misfits

and it followed them through a brief and bloody career in banditry.

Baby Bandits — it must have been humiliating for youngsters in their late teens to read

that term. Nevertheless, a clever reporter gave the name to a collection of misfits

and it followed them through a brief and bloody career in banditry.

Thanksgiving 1936 segued to a fretful weekend for residents of the San Francisco Bay Area. Apparently, a gang of hooligans — bold, brash and armed with deadly weapons — was on the loose. No one knew how many — eight, twelve, twenty — were in the gang. It moved quickly, struck at random and covered a wide swath of territory. Descriptions ran the gamut — tall, short, fat, lean. Agreement converged on a single point: the outlaws were young. The police traced nearly a dozen armed robberies to the hoodlums, all with similar modus operandi. Nevertheless, uncanny luck coupled with misinformation and incorrect assumptions made by law enforcement agencies, kept the bandits a step ahead of the law. That the gang numbered eight, twelve or twenty was a fundamental miscalculation. Even the term gang was overblown. Indeed, the Baby Bandits claimed exclusive membership of three malevolent teenagers — Ernest Pla, Frank Sena, and William Daly. Sena was nineteen, Daly eighteen, Pla seventeen. Each was a recent alumnus of Preston Industrial School, a lockup for incorrigible boys at Ione. The trio's reign of terror approached its apex Sunday afternoon. With Pla behind the wheel of a stolen automobile, the boys stopped at a San Francisco tavern to replenish dwindling cash reserves. Pla kept the engine running while Sena and Daly went inside. "Hands up," said the boys. Waving pistols and a shotgun, Sena and Daly ordered patrons to line up with faces pressed against the wall. Daniel O'Connell, a 47-year-old off-duty watchman, was slow to react. His sluggishness cost him his life. Sena lifted the shotgun, pulled the trigger and put a gaping hole in the man's belly. While O'Connell lay in a pool of blood, the tavern was relieved of its cash register receipts and the trio made a clean getaway. Unnerved, perhaps, by the sheer brutality of a senseless killing, Pla left his partners to their own devices and headed for a rendezvous with friends at Merced. At the Southern Pacific Depot in San Jose, temptation got the best of him when ticket clerk J.A. Montague leaned into the safe and manipulated its tumbler. The moment the safe door opened, the 70-year-old clerk felt the barrel of a pistol jabbed into his back. "Get your hands up," Pla told the old man. Instead of complying, Montague whirled around and attacked the gunman. During the skirmish, the pistol fell to the floor. Pla fought his way loose, grabbed the gun and fled the depot. Later, sifting through mug shots at the San Jose police station, Montague was able to identify his assailant. Meantime, Sena and Daly crossed the bay to Oakland. Daylight was fading to dusk when twenty-one-year-old Harold Nickle reached the corner of 36th Avenue and East Eighth Street. His fiancée, nineteen-year-old Irene Bird, was about to leave the car and walk the few steps to her East Oakland home when two youths approached the automobile. The young couple thought the boys wanted directions, and Nickle rolled down the window. Sena opened the door, pressed his gun against Nickle's ribs and said, "Move over." Without another word, he climbed into the driver's seat while Daly opened a rear door and settled against the backseat. Sena put the car in gear and drove away. Moments later, Nickle's mother and sister watched from the front porch of the family home as the car drove by. "That's not Harold driving," said Hanna Nickle to her daughter Helen. "I wonder who it is." "But Harold and Irene are in the front seat with him," observed Helen. Mother and daughter found it curious that Harold and Irene passed the house without waving, but thought no more about it. "Do you know the way to Sacramento?" Sena asked Nickle. The young man said he did and pointed the driver toward Dublin.  Sena leaned back and handed his gun to Daly. Gripping a pistol in each hand, Daly

kept the captives covered. "If you do as we say, you won't get hurt," said Sena.

Sena leaned back and handed his gun to Daly. Gripping a pistol in each hand, Daly

kept the captives covered. "If you do as we say, you won't get hurt," said Sena.

In an odd way, the bandits were considerate and courteous, and not for a moment did it occur to Harold or Irene that they were in the company of killers. Irene thought they were "just a couple of smart kids who wanted to get to Sacramento and stole Harold's car to get there." Certainly, Irene was apprehensive, but she was not afraid. "This is a poor way for you fellows to start out life," she told them. "Why don't you forget about it and go straight? This will never get you anywhere." "It's too late," Sena replied. "This is a kidnapping. We're public enemies now." Whether the comment was boastful or regretful was incidental. Sena's assessment was correct. "Once when Harold and I said something to each other, the fellow in the front seat " remarked, 'Don't you two go planning anything because it won't do you any good.'" Nearing Stockton, Sena decided to make the remainder of the trip on back roads. It was a bad decision. He lost his way and wandered aimlessly for more than an hour. Finally, he asked for directions and Nickle got him back on the right road. On a patch of darkened roadway, Sena pulled over to relieve himself. He took Nickle along and left Irene under the cover of Daly's pistol. The only conversation was a warning from Daly that the gun was loaded and his finger was on the trigger. Later, they stopped to accommodate Irene. "You be back in three minutes," ordered Sena. "I could have yelled to several cars which passed," the young woman acknowledged, "but I was afraid they might shoot Harold." With the lights of Sacramento in the distance, Sena pulled up to a roadside stand. He left the captives in Daly's care and went inside to buy a newspaper. None was available. Beer, however, was available in quantity and he purchased four bottles. He returned to the automobile, passed out chilled bottles of beer and gave Irene a bag of cookies. "Here's something to eat," he said. "I thought you might be hungry." Parked by the side of the road, kidnappers and victims sat in the car and drank beer, watching automobiles speed by. Harold and Irene wondered if unaware policemen were among the passing motorists. After a while, Sena pulled onto the road and proceeded to the outskirts of Sacramento. At about 11:00 o'clock, he stopped curbside near 56th Street and Folsom. On Sena's instructions, all four got out of the car. Daly asked Nickle if he had a driver's license and the young man handed his wallet to the gunman. He took the license and returned the wallet. "Here," said Daly. "We don't want your money." Irene's eye fell on the boy's inappropriate clothing. They were lightly dressed, without hats and appeared cold. "Where are your overcoats?" she asked with motherly concern. "We didn't have time to go home and get them," Sena replied with a hint of defensiveness in his voice. "We have some good clothes but we had to leave them behind," added Daly, slightly embarrassed by his shabby appearance. Sena redirected the conversation to matters at hand. "I know you got to report this," he said, "but we have to meet a fellow in Sacramento and we need forty minutes. If you wait forty minutes before notifying police, we'll leave your car in front of the Bank of America." Harold and Irene agreed — naively. The kidnappers returned to the automobile. As Sena opened the driver's door, he looked back. "If you need any money just say so." Both shook their heads. As he climbed behind the wheel, Sena said, "You're two swell kids." The young couple kept their part of the agreement. They walked to a small coffee shop and ate dinner. After the passage of forty minutes, they took the shop's owner into their confidence and he drove them to the Sacramento police station. |

|

|

|

|

Copyright 2004-2013 by All rights reserved. |